GBZ-Blog 2025

5 June: Looking Towards the Future: The Centre for British Studies Turns 30 in 2025

31 March: Truth in Materials: Looking at Modernism Through Glass

GBZ-Blog 2024

20 September: Womens' Suffrage Literature Workshop

15 July: Panel Discussion: "The 2024 General Election, Results, Politics, and Public Opinion"

2 July: Student Project 2024: "Empire on Display - Reframing the Imperial Legacies of Art"

2 May: "External differentiation: a new trajectory after Brexit and the Ukraine war?"

GBZ-Blog 2023

11 October: New Book: Affective Polarisation - Social Inequality in the UK After Brexit, Austerity, and Covid-19

7 September: The National Health Service and the legacies of empire

26 July: “Sound and Vision: 100 Years of the BBC in Berlin”. A Student Project in Perspective

5 July: The Centre welcomes Evelina to the Academic Staff

30 June: 2023 Annual Conference of the German Association for British Studies

16 May: The Centre welcomes Paolo and Riley to the Academic Staff

1 February: Protecting Life by Investigating Death, Human Rights Obligations on European States to Investigate the Deaths of Migrants and Refuges Sam McIntosh

GBZ-Blog 2022

GBZ-Blog 2021

GBZ-Blog 2020

Looking Towards the Future: The Centre for British Studies Turns 30 in 2025

05 June 2025, Gesa Stedman

Founded 30 years ago as a gift from the Berlin government to the British for their help during the cold war, the Centre for British Studies has developed into a thriving research and teaching institute sporting a wide network. The interdisciplinary and international MA British Studies, unique in Germany and globally, attracts students from around the world. Its alumni work in prestigious Anglo-German and international organisations such as the British Council, the British Embassy or the Deutsch-Britische Gesellschaft, as well as in academia and in firms and institutions in the UK, in Germany, and in other countries. The MA has had one of the longest-standing impacts on internationalisation at HU, with a history going back to a time when universities in Germany were much less interested in crossing geographical boundaries than they are today.

The then Prince of Wales with ambassador Sir Nigel Broomfield,

GBZ founding director Prof Schlaeger and Prof Günter Walch, English Department, HU

The GBZ is home to two international and interdisciplinary research networks, Writing1900 (founded in 2010) with a particular focus on the cultural history of the turn of the century, and the Berlin Britain Research Network (founded in 2014) which concentrates particularly on current affairs in the UK, as well as an early-career literary studies network which was co-founded by GBZ staff, and has a particular interest in classical modernist literature (MADS, founded in 2023). From its founding days onwards, the GBZ has long-standing close relationships with two of the most important British partners of HU, namely the University of Oxford, and King’s College, London.

Currently, and just after a large DFG-project ended which focused on the life and work of the important HU alumnus and lawyer forced into exile by the Nationalsocialists, F.A. Mann, also with an Oxford connection, the GBZ hosts an Oxford-Berlin Einstein-Fellow and his project: Prof. Stefano Evangelista (Oxford) and his research group on “The Boundaries of Cosmopolis”. This grew out of the previous Oxford-Berlin project “Happy in Berlin? English Writers in the City, the 1920s and Beyond”, which led to a five-part podcast, an exhibition at Literaturhaus Berlin, the Bodleian Library, and HU, and a catalogue of the same title. At the moment, and together with colleagues from Charité and Oxford, the GBZ is helping to set up a new interdisciplinary Oxford-Berlin project on ageing.

In recent years, an important highlight was Prof Gesa Stedman’s art project entitled “Afterlives of Empire – Encounters of Art and Academia”, which was part of the GBZ research focus on “Legacies of Empire”, to which GBZ colleagues in law and history also contributed in different ways.

At the moment, students on the MA British Studies, joined by a group of their peers from King’s College, London, are preparing the GBZ’s major project for this year’s Lange Nacht der Wissenschaften on 28 June 2025. Their interactive exhibition and public-facing talks and creative workshops will allow the Berlin audience, including children, to find out about the impact that the so-called Windrush generation had on British society – Caribbean migrants who came to Britain to help the ‘Motherland’ to recuperate after the Second World War. This will be compared to the influence of the ‘guest workers’ from Italy, Turkey, and Greece, who came to West Germany from the 1960s onwards.

The GBZ was founded on the initiative of the British Council, the then British ambassador to Germany, Sir Christopher Mallaby, and professors of English on both sides of the recently fallen Berlin Wall. Although it is much smaller than originally envisaged – it has three chairs rather than six – it has time and again fought tenaciously and successfully against internal and external challenges, supported by its British guest lecturers and the Advisory Board and its prominent members.

Everyday life at the Centre is marked by the actual practice of interdisciplinarity in research, teaching, and knowledge exchange, an openness to reforms and to new topics and agendas, brilliant early career scholars, creativity, a good sense which topics might become important in the future, and a wide-awake and demanding student body. These characteristics promise a future for the GBZ as productive as its successful past. Its current members are therefore optimistic and look towards the next decades with hope, most recently supported by the rapprochement between the UK and the EU which - despite the still palpable consequences of Brexit - might make exchanges between academics as well as student mobility easier.

Truth in Materials: Looking at Modernism Through Glass

31 March 2025, Dr. Sean Ketteringham

On 11th February 2025, the Centre hosted Professor Victoria Rosner (Dean of the Gallatin School of Individualised Study, New York University). Organised to complement Dr Sean Ketteringham’s research as Visiting Fellow on the crosscurrents of architectural and literary modernism, Victoria delivered a lecture titled ‘Truth in Materials: Looking at Modernism Through Glass’.

Victoria’s paper offered a bold new approach to the modernist use of glass and the material’s significance within modernist writing. She proposed glass served as a ‘vehicle for interiority’, undergoing a symbolic shift in the mid-twentieth century from associations with commerce, innovation, and display toward a capacity for self revelation. In the architecture and literature discussed, Victoria suggested glass helped to render the subject available for representation and analysis. This function relied on modernist writing’s ambivalent aspiration to emulate glass despite it ‘weaponization’ in the torpid political climate of the 1930s.

A truly interdisciplinary contribution to current scholarship on the topic, Victoria’s lecture shed light on chronically overlooked proponents of art glass architecture, such as Paul Scheerbart, in conjunction with fresh approaches to Mies Van der Rohe and Le Corbusier. Routed through the insights of Walter Benjamin, these architectural voices were brought into dialogue with literary treatments of glass by Virginia Woolf and William Carlos Williams. In her previous books, Modernism and the Architecture of Private Life (2005) and Machines for Living (2020), Victoria has examined literary-architectural modernist exchange from a variety of angles. The new work she presented to us in Berlin promises an urgent new focus on the materials of modernist constructions of space and interiority.

The lecture was followed by a short response from Sean Ketteringham with a lively Q&A and open discussion with those in attendance.

Women's Suffrage Literature Workshop

20 September 2024, Laura Schmitz-Justen

As part of her research on women’s suffrage novels as Visiting Scholar for the summer term 2024 (April-September), Laura Schmitz-Justen organised an international workshop on women’s suffrage literature. The interdisciplinary workshop was held at the Centre on September 20 and included talks from literary studies, book studies and history. The workshop was met with interest from researchers from Germany, England and the Netherlands as well as from the Centre’s vibrant community of alumni.

The first panel, “Circulating Feminist Ideas,” considered the material networks of distribution for women’s suffrage and feminist politics both in the US and the UK. Ellen Barth (University of Münster) presented on US-American community cookbooks and the question of whether the frequently employed ‘trojan horse’ metaphor for their inclusion of politics is an accurate or useful representation of their engagement with the question of women’s suffrage. Evi Heinz analysed Rebecca West’s literary criticism in The Freewoman (early 1910s) in conjunction with West’s later novel The Judge (1922), which is often named as a piece of women’s suffrage literature. The joint discussion touched on issues of art vs. propaganda, feminist publishing networks and the question of what cultural work publications such as community cookbooks and popular fiction set out to do.

In the second panel, entitled “Women’s Suffrage Literature Then and Now,” Laura Schmitz-Justen (University of Münster) engaged with May Sinclair’s The Tree of Heaven (1917). Her talk argued that the novel builds tension between individualism and collective movements such as the women’s suffrage movement, negotiating a place for women’s suffrage novels and artistic engagement in a climate of ‘deeds not words.’ Turning to a modern-day engagement with the British women’s suffrage movement, Marlena Tronicke (University of Cologne) discussed domestic imprisonment and queer livability in Rebecca Lenkievicz’ play Her Naked Skin (2008). As the first play authored by a woman to be performed on the stage of the Laurence Olivier, the National Theatre’s main auditorium, it raises questions about the status of the women’s suffrage movement in a more recent literary and cultural landscape.

A highlight of the academic programme was the keynote lecture delivered by Dr Helen Sunderland (Leverhulme Early Career Fellow at the Faculty of History, University of Oxford) on “Schoolgirls and Women’s Suffrage in Late Victorian and Edwardian England.” The lecture touched on many points made in previous discussions throughout the workshop, such as the status of ephemeral publications such as school girls’ magazines. Helen Sunderland shed light on how girls engaged with both suffragist and anti-suffragist politics at school. She showcased how discourse of women’s suffrage was a flexible tool which schoolgirls could deploy to their advantage in school publications, performances and mock debates, but also pointed out that schoolgirls were also aware of this discourse’s limits.

Overall, it was an academically stimulating workshop that facilitated many new interdisciplinary and international connections that will hopefully grow to sustain further exchange on women’s suffrage movements.

Panel Discussion: "The 2024 General Election, Results, Politics, and Public Opinion"

15 July 2024, Luca Augé

The 2024 General Election was a historic event in the UK for many reasons. It was the first post-Brexit national election, it was the first TikTok as well as Artificial Intelligence election and, most importantly, it was the first election to produce a change of government in 14 years. After the polls closed on 4 July 2024, the results progressively came and painted a new British political landscape. The Labour Party won 411 seats with a majority of 172 and Keir Starmer was consequentially appointed Prime Minister by His Majesty King Charles III. The Conservative Party was reduced to a third of its original size and won only 121 MPs, leading Rishi Sunak to resign both as Prime Minister and Conservative Party Leader. The Liberal Democrats became the third biggest party with 72 seats followed by the Scottish National Party with 9 seats, Sinn Féin with 7 seats, Reform UK with 5 seats, the Democratic Unionist Party with 5 seats, the Green Party with 4 seats and Plaid Cymru with 4 seats.

To analyse and discuss these election results, a panel was organised by Visiting Fellow and PhD Student in British Politics Luca Augé under the title “The 2024 UK General Election, Results, Politics and Public Opinion”. The aim was to bring together a variety of views from academia as well as journalism and civil society. The four panelists were Dr Tarik Abou-Chadi (Associate Professor of European Union and Comparative European Politics at the University of Oxford), Dr Paolo Chiocchetti (Lecturer and Researcher in British Politics at the GBZ), Alex Forrest Whiting (International News Journalist at Deutsche Welle News) and Jane Golding (Chair of British in Europe as well as of British in Germany and senior EU law specialist). The event started with introductory words from the GBZ Director Prof. Dr. Gesa Stedman and was followed by a discussion for one hour. The panelists discussed the electoral campaign, the implications of the Labour victory for the UK as well for its international partners including Germany and the EU, the Tory defeat and the possible evolution of the Conservative Party, the influence of Reform UK on the right-wing and the electoral success of the Green Party. The panel discussion was followed by 30 minutes of Questions and Answers by the audience, which covered topics like housing, Brexit and security and defence policy. The event was attended by 25 on-site and 35 online participants, which showed the wider interest for the UK election and the GBZ’s role as forum of discussion.

For the event details, please go to: https://www.gbz.hu-berlin.de/events/gbz_poster_general-election-panel-15-july-24.pdf

Student Project 2024: "Empire on Display - Reframing the Imperial Legacies of Art"

2 July 2024, Evelina Bazaeva

How can we recast the legacy of colonial encounters that shaped the British imperial project in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries? Can art be used as a tool for interpreting colonial violence? In what ways can we interrogate the role that practices of display and the portrayal of colonial art and artefacts play in today’s society? These are the questions that guided this year’s student project, “Empire on Display: Reframing the Imperial Legacies of Art”, undertaken by the MA British Studies class of 2023/25 as part of their Cultural Project Management (CPM) course.

As one of the 170 projects offered by 60 other participants of the Lange Nacht der Wissenschaften 2024, Empire on Display took place in the Lichthof Ost of the main building of Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin, welcoming almost 200 guests from 5pm till midnight. The event programme encompassed five main parts: bilingual exhibition tours in German and English, an illuminating panel discussion, an engaging art workshop, expert mini-talks with doctoral researchers, and a postcolonial quiz. The exhibition, produced and curated by the students, took the visitors on a journey through the subaltern narratives of British colonialism — Indian, Egyptian, Irish, Caribbean, Australian, and New Zealand — and the dual narratives of coloniser and colonised. With the help of student guides, the attendees thus engaged in a critical conversation about restitution debates, the legacies of slavery, the origins of border conflicts, and other topics. The ensuing panel discussion “Revisiting Afterlives of Empire – Encounters in Art and Academia” centred around the artworks of Dr. Karin Stumpf (Akademie für Malerei Berlin), Chen Chen (the University of Oxford), and Claudia Gattner (Akademie für Malerei Berlin), exhibited throughout the evening for the occasion. This allowed the participants to explore the art pieces in detail and hear from the artists themselves about their personal and professional work, their contribution to the decolonisation of art, and their involvement in “Afterlives of Empire”, an original project curated and conceived of by Prof. Dr. Gesa Stedman in 2023. Afterwards, the visitors were invited to join forces with Karin, Chen, and Claudia as part of the highly-attended workshop and jointly produce a unique work of art through collage.

For the mini-talks on ethnography, anti-imperialism & the effects of knowledge on art perception, the students and guests were joined by doctoral researchers Joanna Vickery-Barkow (Princeton/HU) & Hannah Kaube (HU), who engaged in an interdisciplinary dialogue about the imperial entanglements of Western museums, restitution and repatriation, and neuroscientific responses to the knowledge of the artefact’s problematic provenance.

The event concluded with an interactive postcolonial quiz interrogating the past histories of colonialism still present in everyday life. Aside from the scheduled programme, the participants seized the opportunity to create collages using artworks, newspapers, and advertisements from the British empire at the postcard station, reframing and approaching those critically, while crafting a souvenir to take home.

During the event, the students and staff of the Centre were honoured by the visit of the President of the Humboldt Universität zu Berlin, Prof. Dr. Julia von Blumenthal, and Vice President for Finance, Human Resources and Operations, Niels Helle-Meyer, who kindly joined the rest of the attendees for a guided tour and other activities prepared by the students in anticipation of the President’s attendance. The event was made possible by the generous support of Humboldt-Universitäts-Gesellschaft and the Centre for British Studies.

During the event, the students and staff of the Centre were honoured by the visit of the President of the Humboldt Universität zu Berlin, Prof. Dr. Julia von Blumenthal, and Vice President for Finance, Human Resources and Operations, Niels Helle-Meyer, who kindly joined the rest of the attendees for a guided tour and other activities prepared by the students in anticipation of the President’s attendance. The event was made possible by the generous support of Humboldt-Universitäts-Gesellschaft and the Centre for British Studies.

The packed auditorium of Lichthof Ost and the overwhelmingly positive feedback from the attendees served as testament to the successful outcome of the course, made months of planning and preparation most worthwhile, and added yet another student project to the already rich tradition of the Centre’s contributions to the Lange Nacht der Wissenschaften.

"External differentiation: a new trajectory after Brexit and the Ukraine war?"

2. May 2024, Dr Paolo Chiocchetti

Paolo Chiocchetti won a small DFG grant for his research project “External differentiation: a new trajectory after Brexit and Ukraine?” (2024, principal investigator, 20,018 euro).

The 1-year project will carry out a systematic reassessment of the historical evolution, forms, drivers, and consequences of ‘external differentiated integration’ (Schimmelfennig & Winzen 2020; Sielmann 2020), exploring how the relations between the European Union and third countries have changed since the 1990s and identifying an emergent shift since the Brexit process and the Russian invasion of Ukraine. The work will result in a special issue for the journal West European Politics (WEP) and in plans for a larger follow-up grant.

As a first step toward these aims, an international workshop with 14 political, legal, and historical scholars was held at our Centre in Berlin on 18-19 January 2024.

An introductory session included institutional greetings from Gesa Stedman (Humboldt, Centre for British Studies), Silvia von Steinsdorff (Humboldt, Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences), and Paolo Chiocchetti as well as the presence of a delegation from ZOiS Berlin (Gwendolyn Sasse and Julia Langbein). The first panel focused on conceptual and theoretical issues, with papers by Stefan Telle (Twente), Sandra Lavenex (Geneva), and Maria Patrin (EUI Florence). The second panel examined different forms of EU external relations, with papers on the European Neighbourhood Policy (Tobias Schumacher, NTNU Trondheim), preferential trade agreements (Andreas Dür, Salzburg), and the Brexit negotiations (Stefan Telle, Twente). The third panel zoomed in on the current accession agenda in Eastern Europe, with papers on Turkey (Meltem Müftüler-Baç, Sabancı Istanbul), the Western Balkans (Maria Giulia Amadio Vicerè, LUISS Rome, and Matteo Bonomi, IAI Rome), and Ukraine (Maryna Rabinovych, Adger). The fourth panel discussed developments in the old neighbourhood in Western Europe, with papers on Norway (Kristine Graneng and Lise Rye, NTNU Trondheim), Switzerland (Sieglinde Gstöhl, CoE Bruges), and the UK (Federico Fabbrini, DCU Dublin). In a final session, Stefan Telle summarized the lessons learnt and set down the agenda for future activities and deadlines.

An introductory session included institutional greetings from Gesa Stedman (Humboldt, Centre for British Studies), Silvia von Steinsdorff (Humboldt, Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences), and Paolo Chiocchetti as well as the presence of a delegation from ZOiS Berlin (Gwendolyn Sasse and Julia Langbein). The first panel focused on conceptual and theoretical issues, with papers by Stefan Telle (Twente), Sandra Lavenex (Geneva), and Maria Patrin (EUI Florence). The second panel examined different forms of EU external relations, with papers on the European Neighbourhood Policy (Tobias Schumacher, NTNU Trondheim), preferential trade agreements (Andreas Dür, Salzburg), and the Brexit negotiations (Stefan Telle, Twente). The third panel zoomed in on the current accession agenda in Eastern Europe, with papers on Turkey (Meltem Müftüler-Baç, Sabancı Istanbul), the Western Balkans (Maria Giulia Amadio Vicerè, LUISS Rome, and Matteo Bonomi, IAI Rome), and Ukraine (Maryna Rabinovych, Adger). The fourth panel discussed developments in the old neighbourhood in Western Europe, with papers on Norway (Kristine Graneng and Lise Rye, NTNU Trondheim), Switzerland (Sieglinde Gstöhl, CoE Bruges), and the UK (Federico Fabbrini, DCU Dublin). In a final session, Stefan Telle summarized the lessons learnt and set down the agenda for future activities and deadlines.

11 October: New Book: Affective Polarisation - Social Inequality in the UK After Brexit, Austerity, and Covid-19

7 September: The National Health Service and the legacies of empire

26 July: “Sound and Vision: 100 Years of the BBC in Berlin”. A Student Project in Perspective

5 July: The Centre welcomes Evelina to the Academic Staff

30 June: 2023 Annual Conference of the German Association for British Studies

16 May: The Centre welcomes Paolo and Riley to the Academic Staff

1 February: Protecting Life by Investigating Death, Human Rights Obligations on European States to Investigate the Deaths of Migrants and Refuges Sam McIntosh

New Book: Affective Polarisation - Social Inequality in the UK After Brexit, Austerity, and Covid-19

11. October 2023, Professor Gesa Stedman

As a further output generated by the Berlin Britain Research Network, Gesa Stedman and Jana Gohrisch have edited this co-authored book, which was published by Bristol University Press in September 2023. Building on the model of the previous book Contested Britain: Brexit, Austerity and Agency, also published with BUP, an online author workshop took place with most of the contributors attending. Key concepts such as affective polarisation, as well as case studies were debated, thus ensuring a coherent book and a cross-disciplinary dialogue between more historically-oriented writers and those who, as social scientists, initially tend to look more towards the present. The result, which has a distinctly cultural-studies twist to it, received praise not only from its external readers but is apparently already being consulted for a current PhD project in the social sciences. It is also in part available on Google Books. The latter is a more dubious achievement, as we would prefer the book to be bought, not least by libraries, rather than be pirated online. But what counts most, of course, is engaging with the ever-more pressing topic and reality of social inequality in Britain which unfortunately does not stand much chance of being overcome in the near future.

As a further output generated by the Berlin Britain Research Network, Gesa Stedman and Jana Gohrisch have edited this co-authored book, which was published by Bristol University Press in September 2023. Building on the model of the previous book Contested Britain: Brexit, Austerity and Agency, also published with BUP, an online author workshop took place with most of the contributors attending. Key concepts such as affective polarisation, as well as case studies were debated, thus ensuring a coherent book and a cross-disciplinary dialogue between more historically-oriented writers and those who, as social scientists, initially tend to look more towards the present. The result, which has a distinctly cultural-studies twist to it, received praise not only from its external readers but is apparently already being consulted for a current PhD project in the social sciences. It is also in part available on Google Books. The latter is a more dubious achievement, as we would prefer the book to be bought, not least by libraries, rather than be pirated online. But what counts most, of course, is engaging with the ever-more pressing topic and reality of social inequality in Britain which unfortunately does not stand much chance of being overcome in the near future.

The book can be ordered here: Click to see

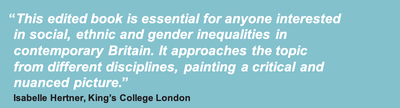

"The National Health Service and the legacies of empire

7. September 2023, Professor Miles Taylor

At the beginning of October, the GBZ is hosting a two-day international symposium to mark the 75th anniversary of the British National Health Service (NHS). The event focuses on a neglected theme in the organisation’s history, culture and current medical practices. The NHS and the legacies of empire investigates the influence of race, colonialism and migration on different aspects of public health in the UK from 1948 through to the present day. The NHS is an iconic British institution, its central place in public consciousness demonstrated during the recent Covid19 pandemic by the slogan ‘Save the NHS’ and the weekly ritual of millions of Britons standing outside their homes to applaud its work. The NHS remains a powerful reminder of national unity at the end of the Second World War and the political consensus around the welfare state which dominated the second half of the 20th century. Although the reliance of the NHS on people from a black and minority ethnic (BME) background is well-documented (22.4% in 2021), the wider cultural, historical and medical context of this phenomenon is under-investigated.

The NHS does not lack histories and scholarly study. However, until relatively recently the contribution of racial minorities to the NHS did not feature significantly in the principal accounts of the NHS. Two recent developments have begun to change perspectives. Firstly, the black staffing of the NHS was foregrounded by the political controversy in 2018 over the rights to UK citizenship of the so-called ‘Windrush’ generation, that is to say, the migrant workers who were recruited from the Caribbean for employment in the NHS (and other parts of the public sector) and who arrived in London on the boat named ‘Windrush’ in June 1948. Secondly, in 2020-22 Covid-19 made a disproportionate impact on BME health professionals and the UK BME population more generally. Widespread evidence emerged of higher rates of immunodeficiency amongst BME workers and families, based partly on a historically greater prevalence of diabetes, cardio-vascular disease, as well as poorer access to health-care. Research also showed that that the BME population were less likely to participate in clinical trials, and that over a longer historical period, illnesses that affected them disproportionately, such as sickle-cell anaemia, received less attention in medical research. In response to ‘Windrush’ and BLM, and to Covid-19, there has been a sea-change in scholarly work and civic engagement on the subject of the NHS, race, colonialism and migration. The chief funding agencies responsible for research in medicine and in the medical humanities, namely UKRI, the Wellcome Trust and the Nuffield Trust have all prioritised the investigation and discussion of these topics, as have the main professional bodies such as the Royal College of Nursing and the British Medical Association. A symposium devoted to publicising and discussing this recent proliferation of interest in the NHS and race is therefore timely.

By showcasing recent scholarly research and community projects this GBZ symposium has four main aims. 1. To highlight how the NHS was established and developed during Britain’s transition from Empire to Commonwealth; 2. To understand better the impact of health inequalities on BME communities in the UK; 3. To compare the colonial legacies within the NHS with the modern German public health system; and 4. To debate the future of the NHS with health policy experts.

For the draft programme, please go to: https://www.gbz.hu-berlin.de/events

"Sound and Vision: 100 Years of the BBC in Berlin". A Student Project in Perspective

26. July 2023, Chris Dolphin, MA British Studies student & Head of CPM PR Team (2023), & Evelina Bazaeva

Beginning in the winter semester of 2022, the students of the Centre for British Studies laid the groundwork for the multi-faceted student project, Sound and Vision: 100 Years of the BBC in Berlin, as part of their course on Cultural Project Management, led by lecturer Evelina Bazaeva. This year, the event was a celebration of the BBC’s centenary in 2022 and featured a thematic exhibition, a panel discussion with German and British academics, a short student documentary, and a podcast series. The event was hosted at the Jacob-und-Wilhelm-Grimm-Zentrum here in Berlin on the 2nd of June.

As the project progressed, the class showcased their talent, skills, and knowledge of the BBC’s role in Berlin’s history over the course of 100 years. It culminated in an informative and entertaining event, enjoying success with both a live and remote audience. The students connected Berlin’s past and present through the lens of radio and reportage of the BBC during the interwar period, the war years, and the Cold War through the eyes and insights of scholars, politicians, journalists, and ordinary Berliners.

The event was inaugurated with the exhibition which unveiled the BBC’s role in shaping the music and radio landscape of Berlin and was displayed in the foyer of the Grimm-Zentrum for two weeks. The documentary, Berlin Through the Lens of the BBC: A Century of Reporting and Reflection, presented a historical overview of the BBC’s reportage in Berlin by drawing on interviews with the local people who experienced the Cold War, as well as German and British historians and media scholars. The podcast, the GBZ Rundfunk Retrospective, offered insights into the critical history of the personalities that made the BBC while having deep ties with the German capital. The episodes featured interviews with Ben Bradshaw MP, a former BBC correspondent in Berlin and long-standing member of the Centre’s Advisory Board, Dr. Emily Oliver (Magdalen College School, Oxford), Dr. Stephanie Seul (University of Bremen), and Professor Richard Aldous (Bard College, New York). You can find out more about the event and get access to our project media on our Instagram page at @british_berlin.

The Centre welcomes Evelina to the Academic Staff

5. July 2023, Prof Dr Gesa Stedman

The Centre for British Studies is delighted to welcome a new member to its academic staff.

Evelina Bazaeva started her role as Lecturer and Researcher in British Culture and Literature at the Centre for British Studies in March 2023. She received a first-class degree in BA Linguistics in 2018 and holds an MA in British Studies with distinction from Humboldt Universität zu Berlin. Following her internship as teaching assistant at Queen Mary University of London and graduation from the Centre, she went on to pursue a PhD under the joint supervision of the Faculty of English and American Studies and the Centre for British Studies. Her research focuses on the intersection of interwar British women writing and film theory in the early 20th century and the broader role of intermediality in Anglo-American modernisms.

Evelina Bazaeva started her role as Lecturer and Researcher in British Culture and Literature at the Centre for British Studies in March 2023. She received a first-class degree in BA Linguistics in 2018 and holds an MA in British Studies with distinction from Humboldt Universität zu Berlin. Following her internship as teaching assistant at Queen Mary University of London and graduation from the Centre, she went on to pursue a PhD under the joint supervision of the Faculty of English and American Studies and the Centre for British Studies. Her research focuses on the intersection of interwar British women writing and film theory in the early 20th century and the broader role of intermediality in Anglo-American modernisms.

After receiving the DAAD Fellowship for Completion of Degree in 2021, she spent two terms as a visiting PhD researcher at the University of Cambridge as part of the Erasmus + Mobility programme. This year, her project has been awarded funding by the Oxford-Berlin Research Partnership, which will result in a research trip to the archives of the University of Oxford. She is currently working on her thesis, along with other projects pertaining to the field of comparative literature, the history of the novel, and intermediality.

As a member of the Centre’s academic staff, she has taught courses on Academic Writing and Cultural Project Management (CPM).

2023 Annual Conference of the German Association for British Studies

30. June 2023

The 2023 Annual Conference of the German Association for British Studies (AGF), devoted to “Political culture and culture politics in the UK: practices, ideologies, and imaginaries”, was held at our Centre on 19-20 May.

The two-day interdisciplinary event saw presentations by 15 researchers from German, British, and other European universities and explored the mutual relation between culture and politics through the concepts and methods of History, Political Science, and Cultural Studies. The contributions highlighted the salience and pervasiveness of ‘cultural’ issues in British political debates and the fruitfulness of an interdisciplinary approach to political culture.

The conference was preceded by the annual Early Career Workshop of the association, in which five doctoral students discussed their developing research on 19th century and early-20th century British history.

PROGRAMME

AGF ANNUAL CONFERENCE

WELCOME: POLITICAL CULTURE AND CULTURE POLITICS IN PERSPECTIVE

Kirsten Forkert (Birmingham City University)

Marius Guderjan (Freie Universität Berlin)

PANEL I: IMAGINARIES (chair: Hannah Jones)

Paolo Chiocchetti (Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin) The Convergence of Brexit and Partisan Identities: Ideological Sorting or Adaptation?

John Clarke (Open University) Defending “Our History”: Contested National Imaginaries in the UK

Zaki Nahaboo (Birmingham City University) Unforeignness “After” Empire: A Genealogy of British Citizenship

Daniel Ziesche (Chemnitz University of Technology) Class, ‘Valence’, and Emotions in English and German Political Culture

PANEL II: PRACTICES (chair: Kirsten Forkert)

Marc Geddes (University of Edinburgh) Parliamentary Traditions in the UK: Exploring Beliefs, Practices and Dilemmas to Explain Change and Continuity in the House of Commons

Nikolai Wehrs (Universität Konstanz) Omnishambles! The Decline of the Civil Service Tradition and the Ascent of Party- Political Special Advisers in the United Kingdom since the 1970s

Hannah Jones (Warwick University) and Christy Kulz (Technical University Berlin) “Ain’t No Black in the Union Jack”, Generation Z: Children and young people’s political and civic responses to Britain’s “culture wars”

Pierre d’Alancaisez (Birmingham City University) The Long March through the Institutions at the Crossroads: What Next for Cultural Politics?

AGF DISSERTATION PRIZE

Thomas Querijn Menger (Universität zu Köln) The Colonial Way of War: Extreme violence in knowledge and practice of colonial warfare in the British, German and Dutch colonial empires, c. 1890-1914

KEYNOTE LECTURE

Maria Grasso (Queen Mary University of London) Political Generations, Socialisation and Changing Values in the UK

PANEL III: IDEOLOGIES (chair: Christy Kulz)

Carlo de Nuzzo (Sciences Po Paris) Right-wing Populism: Style or Doctrine?

Sebastian Althoff (University of Paderborn) “I detest the Tories”: The Discursive and Affective Boundaries of Democratic Debates

Alan Convery (University of Edinburgh) Neverland: The Strange Non-Death of Cakeism in Conservative Thought on Europe

Antonios Souris (Freie Universität Berlin) Cooperative federalism, multiparty governments, and populism in Germany

DISCUSSION: POLITICAL CULTURE – WHAT’S NEXT?

Kirsten Forkert (Birmingham City University)

Marius Guderjan (Freie Universität Berlin)

STRATEGIC MEETING OF THE GERMAN ASSOCIATION FOR BRITISH STUDIES (chair: Christine Krüger)

AGF EARLY CAREER WORKSHOP

PANEL I: 19TH CENTURY (chair: Jonas Breßler)

Felicia Kompio (Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin) Local spaces of protest and order in Bristol at the time of the Queen Square Riots

Claudio Soltmann (Johannes Gutenberg-Universität Mainz) Hannibal Evans Lloyd as a Cultural Mediator between Britain and the German States: The Case of the London Literary Gazette (1817-1827)

PANEL II: WWI AND INTERWAR PERIOD (chair: Lea Levenhagen)

Sarah Fißmer (Universität Bonn) Framing Reconciliation on the Western Front: The Discourse of Reconciliation in Current British Remembrance Practices at First World War Lieux de Mémoire

Chantal Sohrwardy (Technische Universität Dresden) Britische Kriegskameradschaft 1914-1938. Emotionen, Praktiken und Narrative.

Jonas Breßler (Johannes Gutenberg-Universität Mainz) Francos Freunde im Westen – Die westeuropäische radikale Rechte und der Spanische Bürgerkrieg.

The Centre welcomes Paolo and Riley to the Academic Staff

16 May 2023, Prof Dr Gesa Stedman

The Centre for British Studies is delighted to welcome two new members to its academic staff.

Dr. Paolo Chiocchetti joined the Centre in November 2022 as Lecturer and Researcher in British Politics.

Paolo obtained his PhD from King’s College London and subsequently held postdoctoral positions at the University of Luxembourg, Humboldt University of Berlin, and the European University Institute in Fiesole. A specialist in British and European politics, his recent publications include the monograph The radical left party family in Western Europe, 1989–2015 (Routledge, 2017), the edited book Competitiveness and solidarity in the European Union: interdisciplinary perspectives (Routledge, 2019), and the article ‘A quantitative analysis of legal integration and differentiation in the European Union, 1958–2020’ (JCMS, 2023). He is currently working on a series of peer-reviewed articles on Brexit identities, leadership in the Labour party, and differentiated European integration.

His responsibilities at the Centre will include the teaching of MA courses (‘Constitutional Law and Political System’, ‘Analysing British Politics’, ‘Self, Society, and Agency’, and ‘British International Relations’), the supervision of MA theses on political topics, and the coordination of the work placement scheme.

Riley Linebaugh joined the Centre in January 2023 as Lecturer and Researcher in British History.

Riley obtained her PhD from Justus Liebig University, Giessen and held a position as postdoctoral researcher at the Leibniz Institute of European History in Mainz before coming to Humboldt University. She specializes in the history of British colonial archives and her recent, open access publications include, “’Joint Heritage’: Provincializing an Archival Ideal,” in Disputed Archival Heritage (ed. Lowry, 2022), “Colonial Fragility: British Embarrassment and the So-called ‘Migrated Archives’” (The Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History, 2022) and “Protecting Bad Intel in a Dirty War: Britain’s Emergency in Kenya and the Origins of the ‘Migrated Archives’” (De Gruyter, 2022). She is currently beginning a new project on the participation of female secretaries and spies in the British empire. In addition to her historical scholarship, Linebaugh holds an M.A. in Archives and Records Management and has worked as an archivist in the United States, England and Uganda.

Her work at the Centre includes teaching ‘Explorations in British History’ and ‘Self, Society, and Agency’, both of which focus on primary source analysis in the context of colonial records. She offers MA supervision to students working in history and (post/de-)colonial theory. She assists with the work placement scheme and alumni coordination.

Protecting Life by Investigating Death

1 February 2023, Sam McIntosh

Human Rights Obligations on European States to Investigate the Deaths of Migrants and Refuges

Every year thousands of migrants and refugees are dying unnatural deaths within or close to Europe’s borders. At the same time, there are a number of international and regional human rights obligations on European States to investigate certain types of death. This book presents a comprehensive analysis of the nature and scope of the investigative obligations that arise under five human rights instruments: the European Convention on Human Rights; the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union; the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights; the United Nations Convention Against Torture; and the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child. In doing so, it discusses when these obligations might extend to common scenarios in which unsettled migrants and refugees are dying.

These obligations can be a vital source of public accountability for the realities of migration law, policy and practice, as well as a step on the way to lesson-learning and truth and justice for families and survivors.

The book is caselaw focused and will be of interest to legal practitioners, campaigners, NGOs and academics who are interested in the right to life and associated investigative obligations generally, as well as those who are interested in potential legal avenues in the context of the weekly tragedies that are playing out within and close to Europe’s borders.

The book is caselaw focused and will be of interest to legal practitioners, campaigners, NGOs and academics who are interested in the right to life and associated investigative obligations generally, as well as those who are interested in potential legal avenues in the context of the weekly tragedies that are playing out within and close to Europe’s borders.

Dr. Sam McIntosh wrote this book during his time as a lecturer and researcher at the Centre for British Studies, Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin. Prior to academia Sam worked as a human rights lawyer in firms specialising in civil actions against police and prison authorities, and representing the families of people who have died at the hands of the State.

17 October: Coming soon! Berlin and the BBC Miles Taylor

22 July: What more of English Law and Continental Renaissance? Keval Nathwani

4 July: Promoting the pioneering writer and psychoanalyst Alix Strachey Gesa Stedman

16 February: Happy in Berlin – British Writers in the City 2.0 Gesa Stedman

25 January: The History of Universities Seminar Miles Taylor

Becoming Attached: Sodomy, the Body, and the Origins of Democracy in Early Modern England

13 December, Aylon Cohen

Aylon Cohen is a doctoral candidate at the Department of Political Science at the University of Chicago and a visiting scholar at the Centre, specializing in the areas of intellectual history, democratic, feminist, queer, and critical theory. Aylon’s dissertation project, titled “Becoming Attached: Sodomy, the Body, and the Origins of Democracy in Early Modern England,” studies the historical transition from the rule of the king to the sovereignty of the people in the long 18th century.

My project asks: in an aristocratic world thoroughly suffused by hierarchical chains of subordination and submission at the peak of which the king ruled, how do subjects become attached to and practice revolutionary principles of democratic self-rule in their everyday lives? How do seemingly abstract democratic norms of equality become part of how citizens ordinarily relate to each other? And how should we understand the entangled relationship between intellectual history and the study of ideas with the concrete material practices that made possible the “Age of Democratic Revolutions,” the period from 1760 to 1800 in which the democratic state is said to come into being?

Many historical studies on the transition from monarchy to democracy commonly focus on institutional developments in the economy, state, and/or society to explain the shift away from a state identified with the king’s personal rule. Yet, in focusing on such infrastructural changes, such studies have difficulty explaining how subjects disinvested from the king’s personal rule in order to pledge fidelity and commitment to new political concepts of equality and “the people.” While work in intellectual history regularly centers extra-institutional explanations by attending to the history of concepts and ideas, this scholarship often analyzes political change by concentrating on philosophical texts and their discursive effects on how individuals make sense of the world. Synthesizing these separate emphases on the institutional-material and symbolic-ideational, my work explores the history of political power in Early Modern England by attending to transformations in the material practices and conceptual ideas of the body, the body politic, and bodily feeling. For instance, what do rituals of kneeling and bowing before the king’s body reveal about the representation and reproduction of political authority in the 17th century royal court? What role did emergent practices of bodily intimacy across class boundaries, from the handshake to the hug, play in 18th century transformations to aristocratic relations of subordination and the formation of new egalitarian relations between citizens?

With particular attention to the case of England and its international relationship to France, Holland, and the British colonies, my research makes use of an expansive archive including political pamphlets, juridical treatises, etiquette manuals, newspaper reports, satirical poetry, letters, and engravings to explore the transformation of political life. Their analyses charts an historical arc from the 16th and 17th century royal courts to 18th century republican movements and shows how emerging spaces of political assembly, structured on novel principles of gender, sexuality, and class, reorganized social relations in and through the body and elicited new egalitarian relations of feeling between citizens. Investigating the conceptual and practical role of fraternity and fraternal love in the work of social contract theorists such as John Locke, republican organizations such as the Freemasons, and underground networks of sodomites that contemporaries called Molly Houses, my study shows how political theorists and actors over the course of the 18th century reinvented metaphors of the body politic in order to reimagine principles of political authority and rule while simultaneously developing novel forms of bodily practice to create new relations of equality between citizens.

Coming soon! Berlin and the BBC

17 October, Miles Taylor

Next month the Centre for British Studies is hosting a two-day event, Berlin and the BBC. This international symposium investigates the unique relationship between the British Broadcasting Corporation and the city of Berlin. International scholars from media and film studies, musicology, contemporary history and English literature together with news correspondents will critically assess how German culture and history, filtered through the experiences of Berlin, featured in the programmes and reporting of the BBC over a period of one hundred years. Co-hosted by the Museum Für Kommunikation and the British Embassy, and sponsored by the Deutsche-Britische Gesellschaft and the DFG, the event will conclude with a roundtable featuring BBC Berlin correspondents past and present.

Why has Berlin been so significant for the BBC, and how has the BBC contributed to the lives of the city across the last 100 years? Founded in 1922, the BBC developed strong and influential connections with Germany from the start, focused particularly on Berlin. Germany pioneered radio technology in the 1920s, and the British regarded the principal Berlin radio networks as model examples to follow. The first Director-General of the BBC, John Reith, wanted to broadcast so-called high culture to British radio audiences and often selected Berlin orchestral music for the early live performances of the BBC. By the 1930s, special BBC correspondents were reporting from Berlin. The BBC in Berlin contributed to British attitudes towards the Third Reich, notably through its coverage of appeasement policy and the 1936 Olympic Games in the city. During the second world war, the BBC developed its German Service aimed at listeners across German-speaking regions, but with much of the content derived from and focused on Berlin. And after 1945, the BBC set up its operations in the occupied part of the city, becoming a key institution in the cultural politics of the Cold War, both westward-facing, in transmitting news and features from West Berlin to British and world listeners (and later TV viewers), and also DDR-centred with the continuing activity of the BBC German service. The fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989 and the reunification of Germany in 1990 were hugely significant moments for the BBC, with more radio and TV programmes and news items devoted to Berlin and its redevelopment in the 1990s and 2000s than other news organisations.

As one of the few international cultural institutions that remained in situ in the city throughout the Weimar years, the Third Reich, the era of divided Germany through to the reunification and the return of the capital to the city, the BBC is a potentially revealing case-study of how British-German relations changed over time. We hope that our event will create a fuller understanding of how German culture has been presented to English-speaking audiences, and conversely how British national identity and memory has been formed by images and stereotypes of Germany.

What more of English Law and Continental Renaissance?

22 July, Keval Nathwani, Centre for British Studies

Sir John Baker’s essay English Law and the Renaissance took up the torch left by the early death of the great English jurist FW Maitland in 1906 in his quest to ‘continentalise’ English Law. That is, to show how English Law had been affected and influenced by the jurisprudence of the continent during the intellectual revolutions of the Renaissance. Baker’s use of the word ‘Renaissance’ does two important things. First it suggests that during the Renaissance there was an intellectual phenomenon, alongside the artistic and cultural revolutions, which manifested itself in the modernisation, sophistication, and general increase in legal activity. Part of this process was the centralisation of power through which the bureaucratic administration of legal processes could be more effectively managed. Secondly, Baker’s use of the word ‘Renaissance’ possesses geographic implications. It implies that this revolution in thinking took place ‘over there’ on the continent from which aspects were imported into the English Legal System. Central to Baker’s argument is that “changes taking place on the continent had more in common with those in England than has ever been thought arguable”.

It is from this that I took my research aims for my time at the Centre for British Studies in Berlin. In my Masters research I was particularly interested in the relationship between private property, the late feudal system, and how these were managed by the legal system. In particular by conciliar jurisdiction, or the more famous Star Chamber in the reign of Henry VII 1485-1509. As an equity tribunal Star Chamber could be seen as an aberration in the legal system, a means of shoring up power by the crown dependent of the right to due process by the common law enshrined in Magna Carta. This was true but its use by Henry VII and expansion by Cardinal Wolsey could also be seen to point to new ways of thinking about how legal questions, usually about property, could be solved more efficiently through the direct judgements of the King. Interestingly in the Holy Roman Empire a similar tribunal emerged. It was known as the Reichskammergericht or Imperial Chamber Court, effectively the Supreme Court of the Holy Roman Empire. The Reichskammergericht was effectively founded in 1495 at the Diet of Worms, 1495 during the development of the Imperial Reforms aimed at creating an Ewiger Landfrieden or Perpetual Peace. The parallels in legal thinking are remarkable and have as yet been un-researched. The desire to institutionalise legal norms to create a harmonious national environment, particularly in England after the turmoil of the Wars of the Roses, is perhaps the strongest one. Naturally, there were many differences in the operation of both tribunals, but the fact that they are both established de facto within 10 years of each other with similar legal aims is striking and worth further research.

The sources for such an investigation would present challenges. The records of the Reichskammergericht, were broken up and distributed among the federal states after 1806, the date of the abolition of the Holy Roman Empire by Napoleon Bonaparte, scattering its records across Germany's regional archives. Some of them, therefore, found their way to the Bundesarchiv in Berlin. However, this has, on the whole posed a challenge to research into it despite some well-funded German research projects. However, unlike the records of the Star Chamber they do exist almost in their entirety whereas the Star Chamber book of orders and decrees were lost in the eighteenth century. The variety of sources and other related materiel provide an exciting prospect for such comparative cross border research.

The sources for such an investigation would present challenges. The records of the Reichskammergericht, were broken up and distributed among the federal states after 1806, the date of the abolition of the Holy Roman Empire by Napoleon Bonaparte, scattering its records across Germany's regional archives. Some of them, therefore, found their way to the Bundesarchiv in Berlin. However, this has, on the whole posed a challenge to research into it despite some well-funded German research projects. However, unlike the records of the Star Chamber they do exist almost in their entirety whereas the Star Chamber book of orders and decrees were lost in the eighteenth century. The variety of sources and other related materiel provide an exciting prospect for such comparative cross border research.

The symbiotic relationship between English and Continental legal systems remain very poorly studied. Indeed with Brexit it is unlikely to get much better. What’s more, challenges in language too preclude many British legal historians to contemplate such a comparative approach. It would however be a vast own goal to ignore this hitherto missed opportunity in conceptual approaches to Legal History. The good news is that the wealth of material and ideas are huge and promise fascinating insights and valuable research.

Keval has recently completed his MPhil from the University of Cambridge in Early Modern history and is a visiting scholar at the Centre for British Studies. His interests are broadly English and European legal and constitutional history in the sixteenth century and he chose the GBZ because the cross cultural and broad historiographical interests of the academics, students and other scholars are tremendously intellectually stimulating.

Promoting the pioneering writer and psychoanalyst Alix Strachey

4 July, Gesa Stedman, Centre for British Studies

In the course of my research on Britons in Berlin, which led among other things to a trio of activities: an exhibition “Happy in Berlin? English Writers in the City, the 1920s and Beyond”, a book of the same title and a website (happy-in-berlin.org), I was struck by the lively letters penned by Alix Strachey who spent nearly a year in Berlin in 1924 and 1925. She came to be analysed by Freud’s disciple and close ally Karl Abraham, who had founded the Berlin Psychoanalytic Institute a few years earlier. Strachey threw herself at Berlin’s nightlife, attended seminars and lectures at the Institute, and pursued the translation of Freud’s work into English, together with her husband James Strachey, who had returned to London. Their exchange of letters, although well known to historians of psychoanalysis, also throws a light on post-WWI Berlin and deserves much greater attention.

Long before Isherwood, Auden, and Spender immortalised Berlin, Alix Strachey immersed herself in this ambivalent and contradictory city. More importantly, she wrote about it and in a manner which makes not only for entertaining reading, but also provides a much-needed female perspective. Her accounts of fancy-dress balls and dances, acrimonious discussions amongst the cosmopolitan analysists, her German guesthouse, the difficulties of translation, life as an English café writer in Weimar Berlin and how she met Melanie Klein, are refreshing to say the least. I was therefore glad to be asked to write the biographical sketch on Alix Strachey for the Modernist Archives project, which has just been published. MAPS is particularly interested in the connections to the Hogarth Press and Virginia and Leonard Woolf, for whom Alix Strachey briefly worked before giving up out of boredom. For more detailed information, read the MAPS article here:

https://modernistarchives.com/person/alix-strachey

"EUPL? Never heard of it." - And Why the European Union Prize for Literature is Still Worth a PhD Project

11 March, Anna Schoon, Centre for British Studies

In British Cultural Studies, it can be relatively easy to choose a PhD topic which makes for both exciting research as well as engaging dinner conversations. When writing about films and series, pop artists, or fan culture, a wider audience can easily relate. Undoubtedly, this is not the main purpose of an academic research project. But let’s be honest: knowing that other people share your interest can be motivating and keep you going over the years.

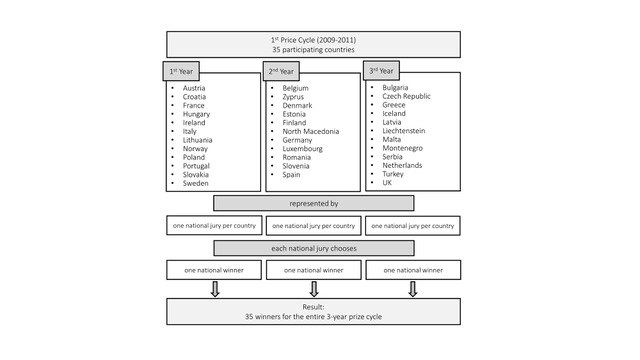

My research, in contrast, was all about the European Union Prize for Literature (EUPL), a literary prize launched by the European Commission in 2009. The usual reaction to mentioning this prize was that people had never heard of it – no matter whether they were well-informed about (contemporary) writing and publishing or had no particular interest in literature. Even some winning authors mentioned that the EUPL came as a big surprise, mainly because they didn’t know it existed. Why did it still make sense to centre my PhD project on this allegedly insignificant prize?

Before answering the question, it is worth briefly introducing the EUPL. This prize is funded by the EU’s cultural programmes, and it is organised by a consortium of literary associations: the Federation of European Publishers, the European and International Booksellers Federation, and the European Writers’ Council. The EUPL, which awards €5,000 to each winner, targets emerging writers of contemporary narrative fiction from the 35–40 countries participating in the EU’s cultural programmes. The prize is also noteworthy for its organisation. Pursuing the aim of “putting the spotlight on creativity and diverse wealth” of contemporary fiction in the greatest number of countries possible, the organisers implemented the following cycle structure stretched over three years:

(A lot can be said about this organisation alone, but that's for another blog post.)

After three years, every participating country has had a winner and the next cycle can begin. In 2021, the EUPL completed its fourth cycle; the fith one was launched in February 2022.

This quick presentation already indicates why the EUPL might not have been a very ‘popular’ prize: the organisation is somewhat confusing at first sight (Who wins? Where? And who selects what?), it is pretty industry-centred, and it privileges national over transnational contexts. Also, the EUPL has not created a huge media buzz. It does not reach more than a few thousand followers on social media (despite a potential audience of several hundreds of millions across Europe and beyond), and it is awarded to emerging authors who do not tend to attract the same amount of attention as literary prizes given to more established writers.

Yet why did I still choose to focus on this specific prize in my research? First of all, because the EUPL has been out there for more than twelve years. Hence, one can assume that it must have some value for the parties involved, even though several voices have pointed to pronounced deficiencies in achieving its declared goals. Secondly, the EUPL is not widely popular, but larger than life in online searches. In Google searches (in English) for ‘European literature EU’, ‘European literature’ or comparable combinations, the EUPL appears as the first (or among the first) search results. Thanks to the influence of search algorithms and web content optimised accordingly, the EUPL has the potential to reach a large audience – independent of any form of (literary) recognition. Another reason to consider it in more detail.

Yet most importantly, the EUPL is representative for a major gap in current literary research on European literature. There has been a consensus that the EU as a concrete political shape of the age-old idea of Europe has raised new questions about European culture and its role for some form of a European identity. However, many scholars with an interest in these questions tend to remain caught up in national models of thinking about culture, identity and legitimacy. Also, there is a strong sense of reservations against the involvement of the EU in cultural matters. The assumption of literary autonomy and that literature must not be instrumentalised by political institutions is prevalent.

Yet these two aspects in particular – unsuitable theoretical concepts and this bias against political institutions – have resulted in the fact that current assumptions foreclose a nuanced debate of the new institutional dimension of European literature. The goal of my PhD project was to open up the discussion again and provide alternative impulses to researching the close interconnection between Europe, the EU and European literature. And the EUPL was the perfect object to explore this issue.

And indeed, my research generated highly relevant insights for this line of research. For example, instead of speaking about ‘the EU’ in a pretty generalised way, one needs to pay attention to what exactly the EU can and cannot do in cultural matters, to who is involved in developing and implementing the existing EU cultural programmes, and how exactly decisions in this context are taken. I also found reasons to challenge the prevailing assumptions of literary autonomy and the national model of identity formation: today, literature, the market and politics are so deeply intertwined (for better or worse) that this changed context – in comparison to pre-EU discourses on Europe – urgently needs to be reflected in future research on Europe, the EU, and European literature. Instead of ‘imagining Europe’, ‘branding’ Europe’ with a special focus on the role of the creative economy, including the publishing world, emerges as a more promising approach.

While the EUPL seems like an unremarkable or even quirky subject at first, a detailed analysis allowed me to explore and eventually start filling a crucial gap in current literary and cultural research.

Happy in Berlin - British Writers in the City 2.0

16 February, Gesa Stedman, Centre for British Studies

The Oxford-Berlin project Happy in Berlin? British Writers in the City has enjoyed an interesting life so far, with three exhibitions, a podcast series, a co-authored book, and various off-shots. The project website has recently seen an update: together with The Stephen Spender Trust, Prof Stefano Evangelista and Gesa Stedman developed teaching materials for teachers of German and English which have recently been uploaded to happy-in-berlin.org.

A-Level students in both British and German schools can work with the map that the website provides, detailing the places which were important for British writers and providing short biographies of famous and not so famous authors such as Virginia Woolf, Alix Strachey, Christopher Isherwood or his friend William Robson-Scott who taught at Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität during the 1930s and was spied upon by his fellow students and Nationalsocialist colleagues at the English department. With a focus on translation, teachers can base their teaching units on texts, authors, and places and explore how writers helped to create the myth of Britons in Berlin which has had a lasting legacy and informs cultural exchange and migration to this day. Virtual school exchanges based on these materials between schools in Oxford and Berlin are planned as a further activity.

A-Level students in both British and German schools can work with the map that the website provides, detailing the places which were important for British writers and providing short biographies of famous and not so famous authors such as Virginia Woolf, Alix Strachey, Christopher Isherwood or his friend William Robson-Scott who taught at Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität during the 1930s and was spied upon by his fellow students and Nationalsocialist colleagues at the English department. With a focus on translation, teachers can base their teaching units on texts, authors, and places and explore how writers helped to create the myth of Britons in Berlin which has had a lasting legacy and informs cultural exchange and migration to this day. Virtual school exchanges based on these materials between schools in Oxford and Berlin are planned as a further activity.

In November 2021, Stefano and Gesa Stedman had the honour of doing a double-act at the Kühlhaus in Berlin Schöneberg as part of the new Oxford-Berlin venture, the Oxford Berlin LiedFest. We talked about the music and sounds which British writers encountered in Berlin, and some of the kind of music they would have heard, or for which they wrote the texts, was performed by passionate and very talented young musicians from Oxford and Berlin. The venue was a former slaughterhouse cooling tower, thus a suitably industrial Berlin space which reminded one of Christopher Isherwood and at the same time of post-WWII Berlin which attracted so many musicians and artists like David Bowie or Nick Cave.

At the moment, we are turning the three exhibitions into a travelling exhibition, based on the structure of the posters shown at HU’s main library foyer last summer. We were also honoured by a favourable review of the accompanying book in the Times Literary Supplement and see further interest being generated by the project. In other words, Happy in Berlin is alive and well and continues to occupy us as well as our audiences and students in interesting and creative ways.

From the Top Down to the Bottom and Upwards Again: the European Integration Cycle of Local Government

7 February, Marius Guderjan, Centre for British Studies

Looking at European integration through the prism of local government might seem a little odd at first. Since the introduction of the Lisbon Treaty major reforms to the EU have been off the table, and the EU has faced a number of regional and global challenges during the last decade; including the Euro crisis, an influx of refugees, climate emergency, a global pandemic, Brexit, autocratic regimes breaking the Union’s fundamental principles and laws, as well as external security threats at the member states’ doorsteps. In response, national governments have returned to more intergovernmental and even unilateral modes of governance to steer through difficult times.

And yet, next to the ‘high politics’ dealt with in Europe’s capitals, politicians and scholars tend to forget that without cities, towns and municipalities EU policies could hardly be realised. Local authorities across Europe are responsible for a wide range of social and economic tasks that are regulated by the EU, including environmental change, energy transition, the integration of refugees, healthcare and other essential public services. Through regulations and directives, but also through policy programmes and funding schemes, local authorities are drawn into the European polity. Policy-makers in Brussels have therefore turned to the local level for effective and innovative ways of developing and implementing their objectives. In particular, the European Commission and the European Parliament clearly acknowledge the essential role of local government for delivering the EU’s agenda.

Local government is not only at the receiving end of policies and laws coming top-down from Brussels. In response to European integration, municipalities adjust their practices, orientation, organisation and politics both internally and externally. Some local authorities and actors engage pro-actively in European affairs and connect themselves in European-wide networks and associations. Although the rise of Euroscepticism in the years before the UK’s EU-referendum had negatively affected the European engagement of English local authorities, we should bear in mind that local authorities in the UK were amongst the pioneers in Brussels and often bypassed the UK Government to deal directly with the EU. Birmingham was the first city to open an office in Brussels in 1984, and by the end of the 1990s, the UK had the highest number of local permanent representations.

Nowadays, local government drives ambitious initiatives that feed bottom-up into European policies around urban mobility, social service provision, environment, procurement, transport, housing. All of this has strengthened the local dimension within the Cohesion Policy and the Urban Agenda. Significant constitutional and procedural reforms highlight the growing role of the local level in the European integration process. The Committee of Regions, the right to local self-government, and the principles of subsidiarity and partnership have promoted local and multilevel governance within the EU’s formal and ‘living’ constitution.

In our book Local Government in the European Union: Completing the Integration Cycle, my colleague Tom Verhelst from Ghent University and I therefore link the macro-trajectories of European integration with micro-developments at the local level. Drawing from a combination of European integration theories and approaches (including intergovernmentalism, functionalism, fusion, post-functionalism, multilevel governance, and Europeanisation), we introduce the idea of an integration cycle to explain how local government responds to the evolution of European governance in different domains and phases.

In our book Local Government in the European Union: Completing the Integration Cycle, my colleague Tom Verhelst from Ghent University and I therefore link the macro-trajectories of European integration with micro-developments at the local level. Drawing from a combination of European integration theories and approaches (including intergovernmentalism, functionalism, fusion, post-functionalism, multilevel governance, and Europeanisation), we introduce the idea of an integration cycle to explain how local government responds to the evolution of European governance in different domains and phases.

Our theoretical explorations suggest that European integration of local government represents a ‘third way’ between an intergovernmental and a supranational perspective. Functional spillover of constraining laws triggers a ‘sovereignty reflex’ to preserve local autonomy, while cultivated spillover shifts the focus of local government towards European agendas. Political spillover then activates a small group of entrepreneurial local authorities and actors, who understand that engaging in European affairs is both a necessity and an opportunity for the future of their municipality.

Considering the vast diversity of local government across Europe, the different stages of the integration cycle do not equally involve all local authorities. Yet, as local pioneers seek to shape and access EU policy-making both formally and informally, local government completes the integration cycle. Subsequently, this may trigger a new loop of top-down and bottom-up dynamics in return.

Brexit and examples from other member states have shown that Eurosceptic politics set clear limits to the integration of all levels. Nevertheless, in times when both long-established and fairly young democracies are challenged by populist and radical movements, cities, towns and counties can be a vital locus of political discourse and legitimacy. Taking municipal insights and preferences better into account can make European governance more effective and in line with local practices. It can also help strengthen the links between citizens and EU institutions. After all, local governments are democratically elected stakeholders within the EU with a clear expertise of dealing with their policy challenges on the ground.

Being in direct touch with their citizens, local authorities take a vital role in overcoming national borders and in contributing to a mutual understanding of differences and similarities. It is in this spirit that our research seeks to improve our understanding of local government in the EU for politicians and people working in public authorities at multiple levels, as well as for academics who may find our empirical and theoretical insights useful for their own endeavours.

The History of Universities Seminar

25 January, Miles Taylor, Centre for British Studies

In 2021, with colleagues from Taiwan, the UK and Australia, I set up an online seminar programme on the ‘History of Universities’. My own interest in this enterprise developed from the book that I co-edited recently: Utopian universities: a global history of the new campuses of the 1960s (Bloomsbury Academic 2020). We identified a ‘gap in the market’. There was no regular seminar series dedicated to the history of universities. There were some well-established annual conferences in the UK, the EU, and the USA. However, most of these were suspended at the time because of Covid-19. Myself and my fellow convenors (Ku-ming Chang, Academia Sinica, Taipei, Taiwan; Heike Jons, Loughborough University, UK; and Tamson Pietsch, University of Technology Sydney, Australia) believe there is a strong new interest in the subject. Leading journals in the field show a proliferation of themes, periods of interest, and historical geographical contexts, and an increasing diversity of authors. There are established and emerging networks of scholars, for example, the Society for Research in Higher Education (UK), CHER (Consortium of Higher Educational Research, Portugal), and the International Commission on the History of Universities. Beyond this, higher education has become an important focus in the history of education, policy and international studies and the history and sociology of knowledge and science.

Moreover, universities are seldom out of the news these days. The general public is increasingly curious about the wider context of where and how academics work and students are educated, and knowledge and innovation are produced and communicated. Since the majority of scholarly work on universities is very presentist, we wanted our seminar series to examine universities in the past, in order to understand better higher education and research in the future. Current challenges include the Covid-19 pandemic; struggles over access and diversity; environmental crisis; austerity and controversial benefactions; the legacies of race and empire; as well as changing geopolitical alliances including Brexit and a more assertive China. All these have historical roots, precedents, or echoes.

We were also determined to make our coverage as international and comparative as possible, reaching back beyond the 19th century, and around the globe. Our initial call for papers invited topics on the history of particular universities, individual disciplines and scholars; practices of research, teaching and learning; scholarly communication, interaction, and networks; students and student movements; universities as communities and sites of ceremony; university design and architecture; universities and society; international relations, philanthropy and political economy; the impact of colonialism; international education.

Our programme was launched in the summer of 2021, in a fortnightly format. Seminar speakers included established scholars, as well as early career researchers. They came from the US, India, and the UK. We included two round-table seminars. One on ‘Universities and slavery’ – dealing with the ‘inconvenient’ pasts of some American and British universities which relied on the profits of the slave trade at their foundation. And another on ‘Universities in years of pandemic: 1665, 1918, 2020’ which compared the present effects of the pandemic with the ‘flu’ of 1919 and the plague of the 17th century.